Abolitionists were a key part of the Civil War era, though it is hard to say that they caused the war itself. Radical abolitionists certainly intensified sectional feelings in the antebellum era. Arguing that American society had become incapable of dealing with the “slave power,” which dominated politics in the economy, post-1830 abolitionists called for more confrontational tactics and strategies to curb bondage in American culture. The speeches of abolitionist Theodore Dwight Weld, the husband of influential female abolitionist Angelina Grimké, are one notable example of the use of this language.

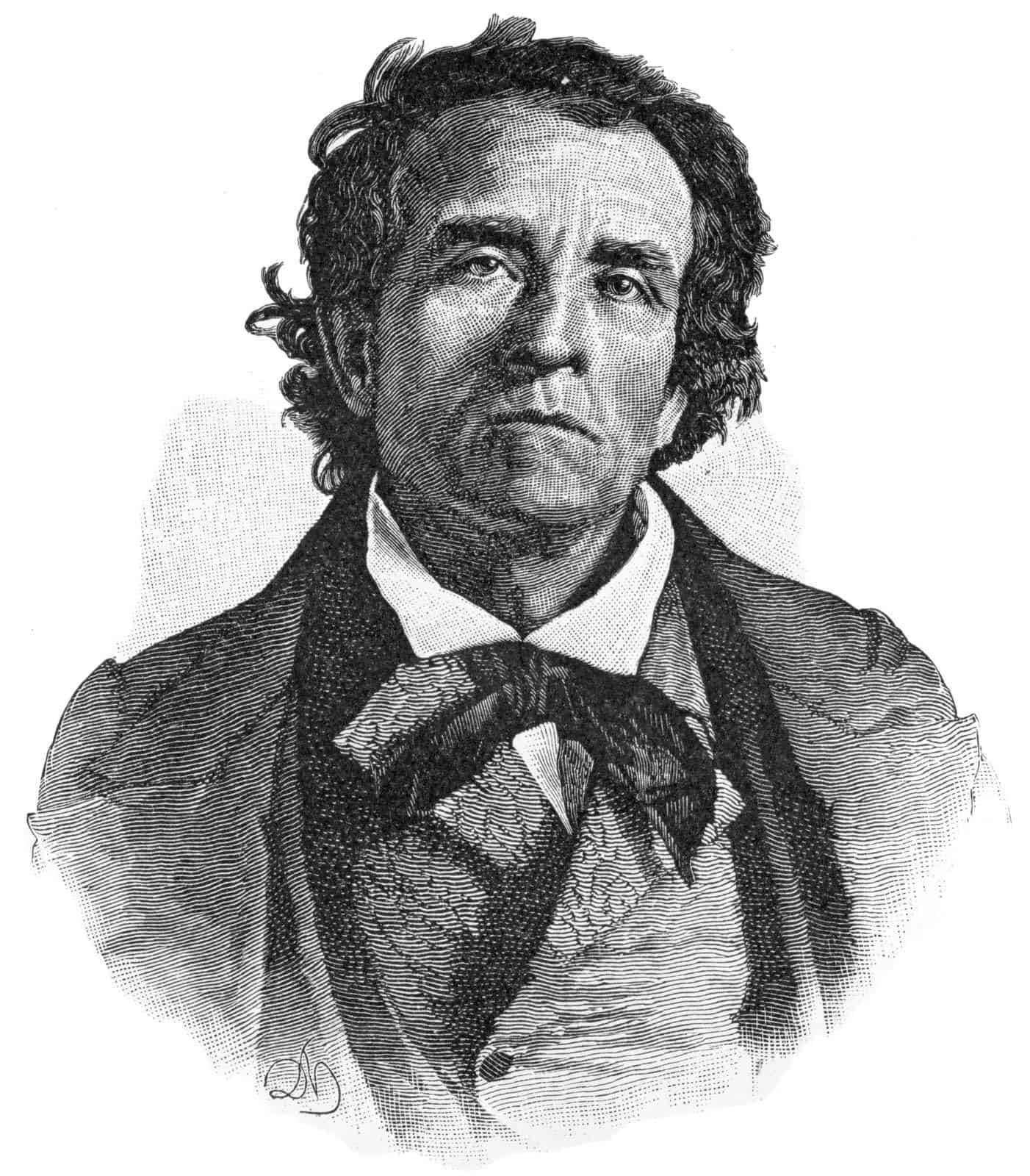

Not only did abolitionists produce more militant attacks on slavery in the years leading to the Civil War, but they often vilified slaveholders themselves as the embodiment of evil. Abolitionists did not form these opinions in a vacuum. Rather, black and white reformers used tales of oppression and violence from enslaved people themselves to argue that bondage violated both scripture and the American creed of equality and justice for all. Abolitionists also cited examples of international emancipation when criticizing American slaveholders. After Great Britain and France issued emancipation edicts in the 1830s and 1840s ending bondage in their colonial possessions, American abolitionists howled that the United States was now the world’s largest slaveholding power. It was true: by 1860, there were nearly 4 million slaves in the United States – more than the next two slaveholding powers (Spanish Cuba and Brazil) combined. “What to the slave is the fourth of July?” asked former slave and noted abolitionist Frederick Douglass in a famous speech in Rochester on July 5, 1852. “A mockery,” he said.

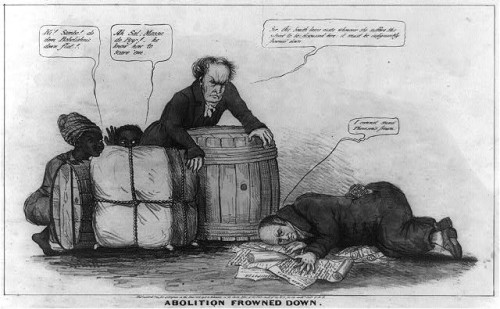

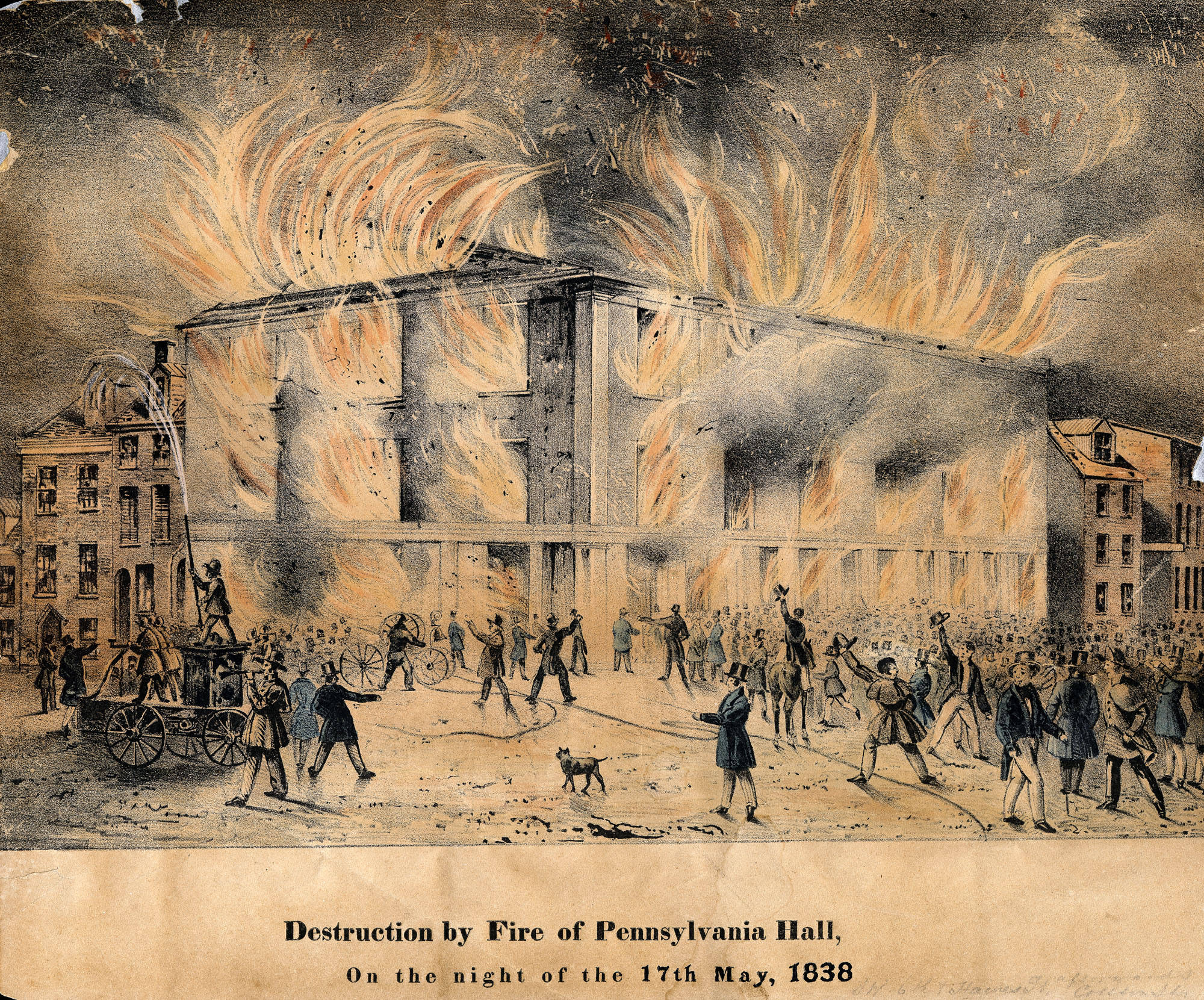

As abolitionists called for more radical attacks on bondage, and began forming political parties that would limit slavery’s expansion in the West, slaveholders and their northern allies vehemently responded. In Congress between 1836 and 1844, a gag rule prevented the discussion of abolitionist petitions. In many northern cities during the 1830s and 40s, anti-abolitionists, fearful that southern emancipation would lead to black migration above the Mason-Dixon line and more fierce competition for free-market jobs, spawned riots that targeted free blacks and abolitionists alike. In 1837 in Alton, Illinois, abolitionist printer Owen Lovejoy was killed by one such mob; the next year in Philadelphia, hundreds of anti-abolitionists gathered outside of Pennsylvania Hall, a gleaming new building dedicated to the abolitionist struggle, to ridicule antislavery men and women. After only four days of operation, the building was torched and never rebuilt.

By the 1850s, sectional violence centered around fugitive slave recoveries. The passage of a stronger fugitive slave law in 1850, which southern masters deemed vital to the security of bondage, prompted a wave of anger throughout the North. With many white citizens radicalized by the law, abolitionists found new friends. Indeed, one might say that the rise of the Republican Party had much to do with residual northern anger over southern political power in the 1850s. When some southerners threatened to leave the Union in the wake of Abraham Lincoln’s election in 1860, more than a few northerners expressed exasperation. Ironically, abolitionists tried to keep a low profile during the secessionist winter of 1860-61. Realizing that southern secessionists appeared to be the new radicals who would destroy the American union, even William Lloyd Garrison argued that abolitionists should let American political events proceed without much further commentary from antislavery figures. This 1862 article from the New York Times illustrates the precarious position of abolitionism in the early years of the war. When 11 states left the Union to form the Confederate States of America, abolitionists asserted that the old union had died at the hands of the slave power. The only remedy for American society was emancipation. As Frederick Douglass put it in May of 1861, the best way to end Civil War was by killing slavery once and for all.

If abolitionists did not cause the Civil War, they shaped its meaning.

Videos

John Brown’s Raid on Harper’s Ferry

Lesson Plans

Life in the North and South, 1847-1861: Before Brother Fought Brother – A complex series of events led to the Civil War. The lessons in this unit are designed to help students develop a foundation on which to understand the basic disagreements between North and South through the investigation of primary source documents.

The Growing Crisis of Sectionalism in Antebellum America: A House Dividing – What characterized the debates over American slavery and the power of the federal government for the first half of the 19th century? How did regional economies and political events produce a widening split between free and slaveholding states in antebellum America? In this unit, students will trace the development of sectionalism in the United States as it was driven by the growing dependence upon, and defense of, black slavery in the southern states.