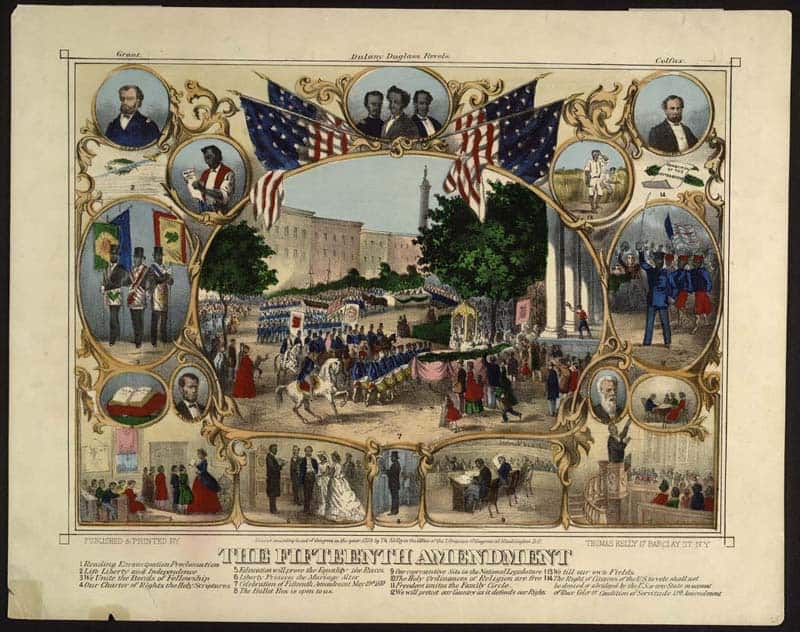

Civil War Americans had multiple responses to emancipation in and beyond the 1860s. At the start of the war, instances of black freedom scared many white unionists, who had long been fearful of southern emancipation.

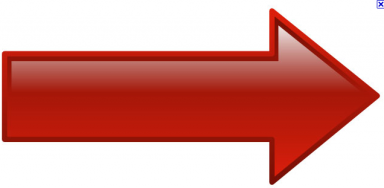

Thus, fugitive slaves arriving in Pennsylvania and New York in 1861 and 1862 were not always greeted with open arms. During the middle of the war, as union fortunes sagged, military commanders, politicians and many members of the body politic shifted course. Agreeing with black and white abolitionists, they supported emancipation as a wartime policy that would destroy the Confederacy. Even northerners skeptical of the Emancipation Proclamation returned Lincoln to office in 1864. Though this had much to do with Union military successes in the deep South, recent scholarship has shown that many white northern soldiers favored wartime emancipation by 1864 and 1865. By the end of the war, in fact, a solid contingent of white Northerners believed that emancipation rationalized the bloodiest conflict in American history. Agreeing with Lincoln that emancipation was just repayment for the sin of slavery, many Americans entered reconstruction with a nearly millennial belief in Civil War abolition. Like a providential offering, emancipation allowed Civil War Americans, including some southerners, to believe the sectional battle had produced a great good in the country.

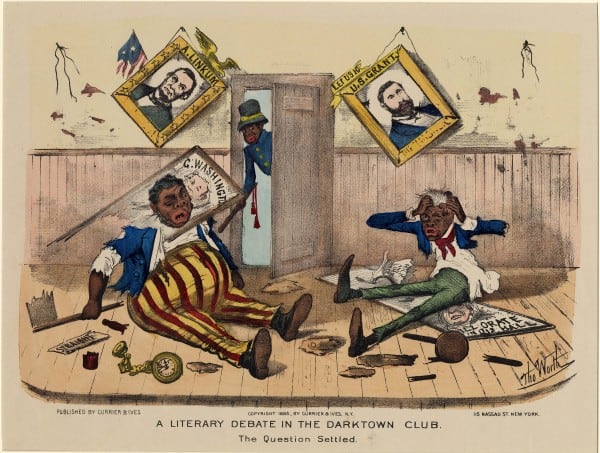

During the 1870s and 1880s, however, American views of emancipation shifted again. For many, abolitionists and African-American reformers, emancipation was not a one-time event but a process that must continue until African Americans North and South were treated equally. Yet many white Northerners tired of emancipation politics after the war. And many southern whites argued that emancipation had actually failed. Drawing on antebellum racial stereotypes, they asserted that blacks were not suited to liberty.

Perhaps equally troubling, whites North and South agreed that reunion had put the problem of slavery firmly in the past; they thus supported the easing of tough Reconstruction policies in the South. Even some abolitionists believed that there were more pressing matters than the legacy of emancipation at the end of the 19th century. As a wave of oppressive laws washed over the post-Reconstruction South, in which African Americans were disfranchised and pushed out of various labor markets, blacks feared that the gains of Civil War emancipation had been lost. Although there was always an American civil rights movement seeking to polish emancipation’s meaning, not until the middle of the 20th century would the liberties of emancipation earn the support of American law.

Lesson Plans

Reconstruction: Rebuilding the Union – This high school level lesson asks students to imagine the difficulties of reuniting a nation torn apart by war. By making connections with contemporary events students will understand the challenges of entrenched racism the late nineteenth century.

Freedmen’s Bureau: Meanings of Emancipation – This elementary level lesson explores the feelings and experiences of emancipation for former slaves as well as the challenges of ensuring freedom after the War.